The Engineering Groundwork for Modern Fashion Design

Written By TFN Writer: Kunal Sheth

A self-deprecating joke amongst many engineers is that we get paid to Google for answers. But I take pride in this— it shows engineering is more instilled in philosophy than banal knowledge.

In the same way, artistic temperament transcends medium, the engineering process is transferable across domains. Engineering and art are a unified discipline built upon technical skills, intuition, and aesthetic sensibility. Thus, it is advantageous to restructure the creative process of garment design using an engineering framework. In this article, I will show how applying an engineering mindset to artistic tradition opens new avenues for improvement.

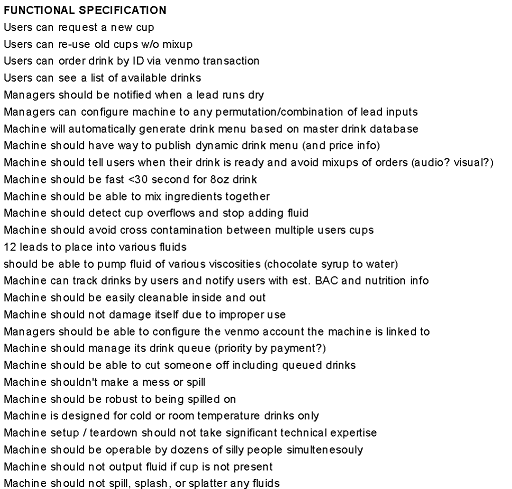

Before attacking any problem, good engineers lay out a requirements specification—a list of desired outcomes, constraints, and optimization factors—as walls for their creativity to bloom within. A good solution satisfies all constraints, and a better solution optimizes for some given factors too.

It is imperative that a “requirements specification” be thorough. Notice how we forgot to mention carbonated sodas in our specification for an automated drink mixer? This oversight led to a thousand-dollar robot that could only serve flat drinks 6 months later, due to faulty assumptions made about air displacement.

What might a thorough requirements specification for a garment look like?

Design is not just about creating a garment that fits and looks good. It is about perfecting a symbiosis of flesh, cloth, motion, and the environment:

Does the garment allow you to move your body in the ways you want to?

Does it stretch, press, pull, and drape in the right places?

Does it require help to put on or take off? Is it even possible to put on or take off? (Surprisingly difficult!)

Does it ever pinch or rub?

Does it tend to ride up or slip down?

Does it interfere with accessories or activities? Wearing a backpack? Washing dishes?

Is it geometrically possible to recreate the 3D garment from 2D fabric given the fabric’s physical properties? Would the necessary seam locations be aesthetically acceptable?

As specifications grow in complexity, the likelihood of producing a complete solution on the first try diminishes. Rather, engineering, like any creative endeavor, is an iterative process that often involves many cycles of trial and error.

Traditionally, a fashion designer might attempt to solve these constraints by:

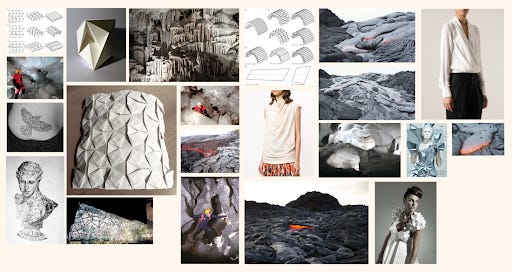

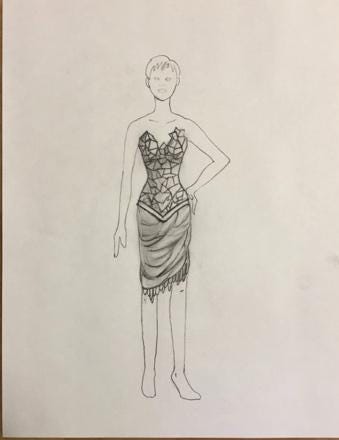

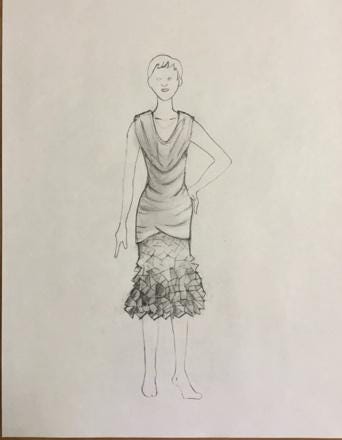

Outlining a target customer and aesthetic. Creating a mood board.

Generating a few croquis sketches and settling on an idea.

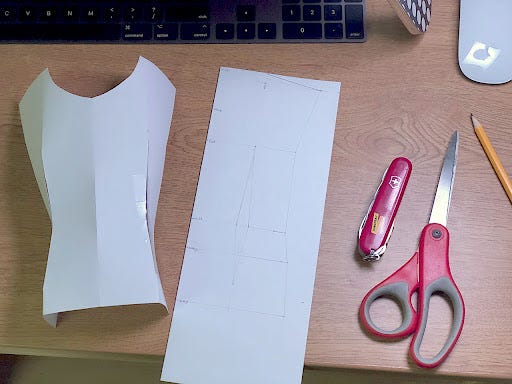

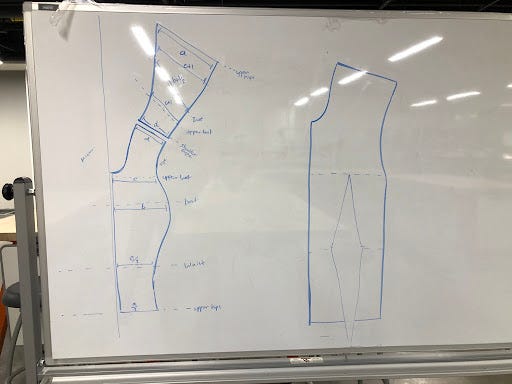

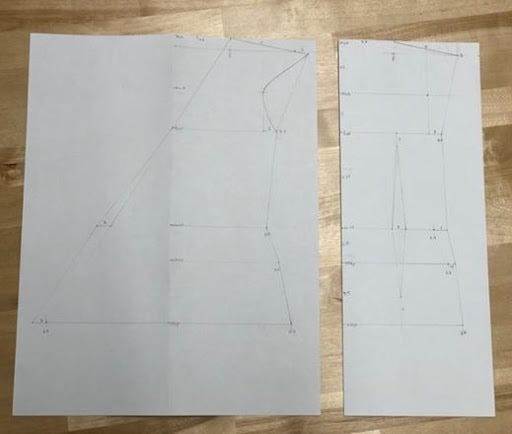

Converting their 3D design into a 2D sewing pattern.

Making a scale model, making tweaks, sewing together a trial piece, fitting their model, making alterations, correcting the pattern, and repeating until satisfactory.

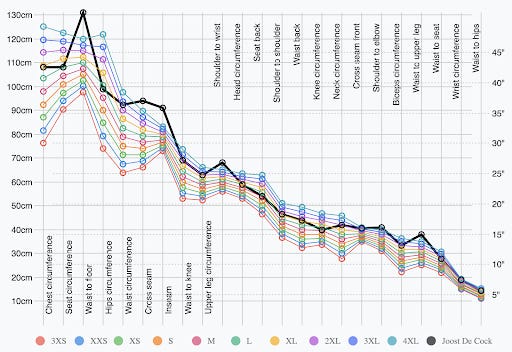

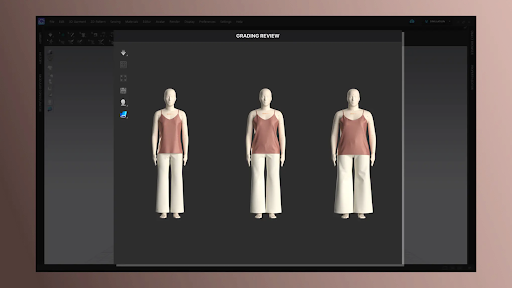

As a solution is incrementally built, new constraints arise and roadblocks get discovered. Sometimes, the variables and constraints become so overwhelmingly complex, that the task becomes impossible. Consider how many measurements, sewing patterns, test pieces, and alterations would be necessary to grade a brand-new design into sizes XS through XXL.

From the graph above, grading a design is not as simple as scaling all the dimensions by some ratio. A human body’s shape cannot be treated like a linear template, even when using the “standardized” sizing scale. A new pattern must be made for each body, a different model must be fitted, and separate alterations made. Each variable multiplies the amount of work needed to be done, eventually turning original designs into an insurmountable problem for today’s fast-paced fashion market. To save money, brands cut corners on plus-sized variations and often tend towards less original patterns.

Fortunately, modern Computer Aided Design (CAD) software solves these problems by providing a 3D virtual sandbox to rapidly design, model, simulate, alter, and experiment. Some engineers may know CAD from classes like SE 101, which teaches hard-surface modeling techniques that have been mainstream for almost three decades.

Link to website: Kunal Sheth

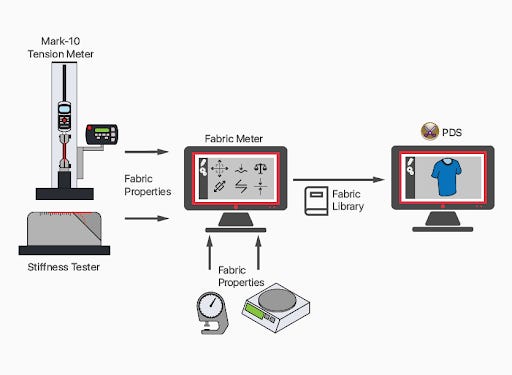

CAD tools for fashion design are quite new, due to the immense computational challenges of simulating cloth and soft bodies. One such challenge is even defining what fabric is. Mathematically, we might say that fabric is a 3D surface that likes to bend but not to stretch. That is, if a piece of fabric starts off flat, we could draw a line between any two random points on it. Then, no matter how we fold, crumple, or bend that fabric, it is reasonable to assume the length of that line will always be the same.

In math terms, we assume all the ways fabric can move, fold, crumple, and bend are locally isometric. Which, by famous 17th-century mathematician Gauss’ Theorema Egregium, means that the gaussian curvature of fabric is constant. Fabric always starts out flat, so the gaussian curvature of fabric should always remain zero.

Put simply, Gauss’ theorem tells us that, if you fold fabric one way, it will become straight along the perpendicular of that fold— kind of like a slice of pizza.

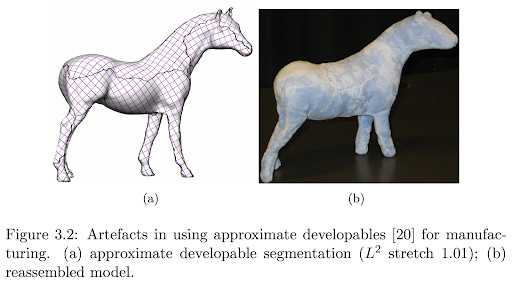

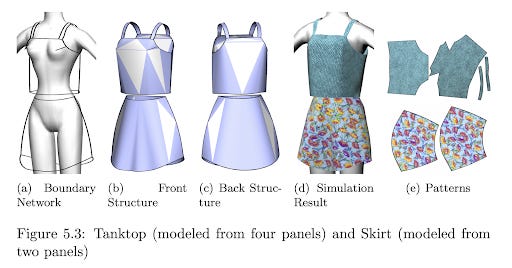

Plenty of research has been done on algorithms to approximate 2D sewing patterns for 3D surfaces using this purely geometric understanding of how fabric behaves. These algorithms will intelligently section off 3D surfaces into low-curvature sub-regions (from our pizza analogy— slices with at least one red line and at most one black line), and then un-bend those regions (straightening the black line) into approximate 2D fabric cuts.

While mathematical purists may love this simplistic model of fabric, anyone who has ever worn skinny jeans knows that fabric can stretch, a lot. Elastic fabrics like stretch denim are intended to press, push, and pull on the wearer’s body. Especially in womenswear, this interaction between body and cloth is of great importance— and must be minutely adjustable by the designer. Our simple geometric model is vastly insufficient for making commercial garments because it does not account for material properties.

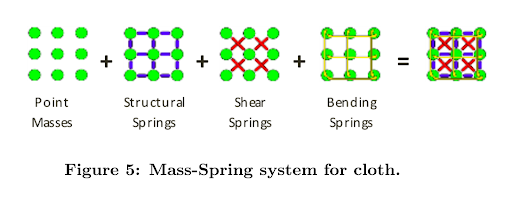

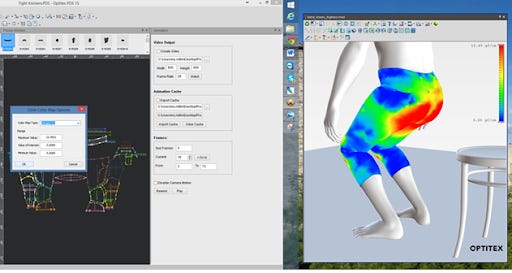

Nowadays, cutting-edge CAD packages like Clo3D and Optitex treat garment design as a physics problem rather than a geometric one. These softwares simulate fabric as a sheet of vertices (masses) connected by edges (damped springs) in 3D space. They also account for complex external interactions like air resistance, collisions, and friction.

Source: Kunal Sheth. A 1,156 vertex cloth simulation I made.

Simulation is a process where, each time increment (say, every 0.01 seconds), all the forces on each vertex are added up and then the vertex is moved by a tiny amount. The more vertices, the more realistic the simulation— and a single garment can have tens of thousands. Due to the huge amount of computing power required, this method of modeling fabric has only recently become possible in fashion CAD packages.

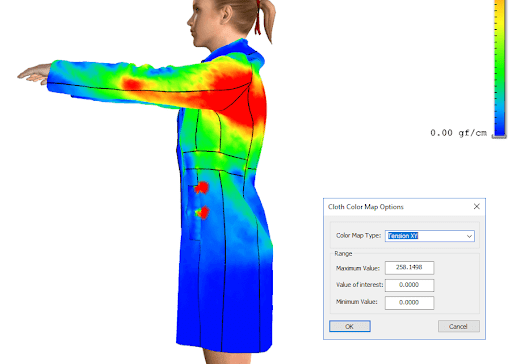

Through simulation, the two-way, simultaneous interaction between flesh and cloth can be accurately modeled. By analyzing simulation data in the form of 3D colormaps, designers can find out even more about their garment than would be possible with a physical version. From both an engineering and fashion design perspective, these cutting-edge industry CAD packages are incredible.

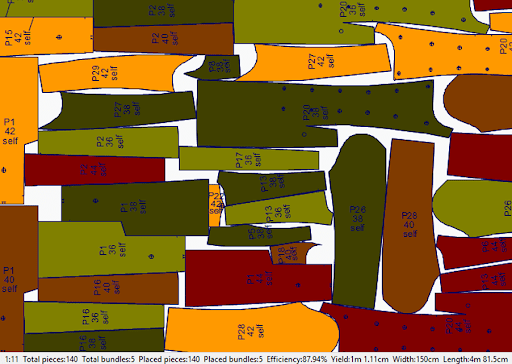

For consumers, the latest generation of simulation-based CAD technology puts real improvements on the horizon. Clothing will start to fit better, especially for plus-sized individuals. Designs can become more diverse as digital tools lower the risk of trying new things. There is even a measurable sustainability improvement thanks to highly efficient shape-packing algorithms included with these tools. By treating engineering and art as a unified discipline, we may preserve the creativity of traditional fashion design while opening up many new avenues for improvement.