A Narrative/Life Cycle of Doc Martens (that my professor said didn't make sense)

By TFN Writer Sabrina Longo

A photo flicked onto the museum projector. Displayed was a sea of raised eyebrows and clasped mouths. There it was. A flash of a security guard flailing backwards onto a crowd of concertgoers. The weapon? A foot armed with a Doc Marten just off-stage. The caption read: The Police in concert. The guitarist, Andy Summers, kicks a guard. 1977. I looked down at my too-shiny Doc Martens. I looked back at his. I looked at mine. In my periphery, there were well-used Docs on the feet of a middle-aged couple beside me, speaking a language I didn’t know. That’s funny. How was it that a 1980s rockstar, vacationing strangers, and I, an American student born in the 2000s, were wearing the same shoes?

Andy Summers (middle) likely taken during the peak of The Police’s career in the ‘80s. Used by the New York Times for a review in 2015. If he was this age today, he would have had a good chance at being White Boy of the Month.

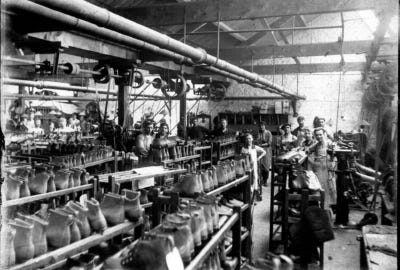

My answer begins at The Cobbs Lane factory run by the Griggs family circa 1960. In Northamptonshire, England, this quotidian brick building is where the first Doc Martens were constructed. Its materials were just as modest: the boot’s not-yet-air-cushioned soles were sourced from the rubber of recycled tire scraps, eventually fused and Puritan-stitched to the shoe’s upper. The upper itself was made from full-grain leather via organic vegetable-tanning, a method as old as cuneiform, out of Manchester’s Wardle Tannery.

Cobbs Lane Factory c. 1930

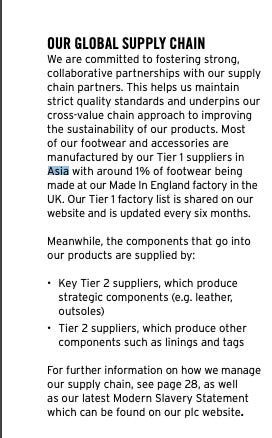

A three-hour drive from Manchester, Summers would have been my age: a rebellious punk sauntering in nearly indestructible, full-grained leather Docs (no polyester “leather” of today’s shoes). They were stomping boots whose humble origins made them a fit symbol for the punk movement’s anti-establishment beliefs. My Docs, conversely, are a symbol — a product, rather — of pro-establishment thinking. The establishment, R. Griggs Group LLC, currently exploits migrant workers in thirteen factories across Asia; almost 70% of footwear is manufactured in Vietnam and China alone. And the old Cobbs Lane factory? Just 1% of the 14 million pairs sold during the 2020 fiscal year. If 1960s punks knew about the Pro-Establishment Shoes I ignorantly slipped on for class, they would find a time machine to stomp me out.

Time-traveling punks would be stunned that I, an American woman, was wearing Docs at all. It wasn’t until 1975 that Doc Martens transgressed continental boundaries with smaller, women’s sizes internationally. This instance of “gender equality,” along with DMs being associated with rock stars like The Police, increased sales exponentially. Such hysteria distracted customers from how they were implicated in the carbon emissions that satisfied such demand. Nevertheless, around 10 pounds of CO2 was emitted for every shoe purchased, five times such value three decades earlier. Generally, 1,600 U.S. imports per year of chrome-tanned hide and petroleum for 7 million boots per year would now tear and crack in as little as three years instead of fifteen. In this way, no longer were customers sustaining the hum of a humble factory or punk’s relevance, but the perpetual winding of capitalism and planned obsolescence. This still stands. I had already gone through two pairs of Docs in five years. The Anti-Establishment, lifetime boot was a phenomenon of the past.

Excerpt from Dr. Marten’s Annual Report for 2023 Fiscal Year that states less than 1% of footwear are made in England (p. 96/236). Read it here : https://www.drmartensplc.com/application/files/8316/8624/2435/Dr._Martens_plc_Annual_Report_2023.pdf#page=64

Yet, as I look at this photograph, the material past is not far off—it is beneath me. Underneath my soles of plastic and PVC, the polyester fibers of museum carpet, the concrete foundation and matted grass. Underneath it all lies the 28th closed landfill in Illinois where my parents’ boots have ended up. A mass grave for 21 years of shoes whose close quarters meant they will never fully decay.

But I didn’t have to take my shoes to the grave. The shoes that walked me and other onlookers through this museum, moments that would become memories, deserved to stay above ground. And so, I took my original question for granted: Andy Summers, the strangers, and I weren’t wearing the same shoes at all. Doc Martens’ modes of manufacturing, consumption, and disposal had varied too immensely across sixty years to make such a generalization. In this moment, Doc Martens as an entity did, however, represent our spontaneous intersection in space and time. And who was I — who are we — to throw that away?